Blood, Belief, and Design: A History of Menstrual Care

Just as menstrual bleeding has been a constant throughout human history, sanitary products have evolved and changed throughout our timeline too. From moss to hypoallergenic mooncups, the history of sanitary products mirrors society’s shifting relationship with menstruation.

Sustainable Ancient Civilisations?

In ancient civilisations, menstruators had to get creative. Ancient Egyptians made ‘tampons’ from rolled papyrus (sometimes filled with herbs and honey) and the Ancient Greeks used sea sponges as a ‘pad’. The repurposing of regenerative natural materials as sanitary products, although inconvenient, made these techniques largely sustainable. However, there is little evidence to indicate how comfortable or uncomfortable these methods were in practice.

Our understanding of these products is speculative, based on small amounts of evidence, but they paint a human picture of the ways menstruators creatively adapted and lived with periods going back thousands of years.

Medieval Times and Taboo

Interestingly, there is a historiological misconception that medieval European menstruators largely free bled. Whilst this may have been the case for those with lighter periods, many are believed to have used moss stuffed linen fabric as a makeshift pad, or even just tied extra cloths under their garments. This goes to show how inventive menstruators had to be whilst using limited and perhaps uncomfortable materials.

This was also a period of increased stigmatisation towards menstruation. For Europeans, periods were associated with the four humours, said to balance human temperament. Given that blood was considered one of these humours, an excess of bleeding was viewed a sign of disease, which increased taboo towards menstruation.

During this time, the subjugation of women became intertwined with religion, and menstrual cramps were often explained as a consequence of Eve’s original sin. This intensified the shame surrounding bleeding, forcing sanitary hygiene into a deeply hidden affair.

Victorian Innovation

This societal stigma surrounding periods continued into the early Victorian era, making the advertisement of sanitary products near impossible. Menstruators continued to use woven flannels, which could be rewashed and re-worn– sustainable, but not the most discreet or convenient.

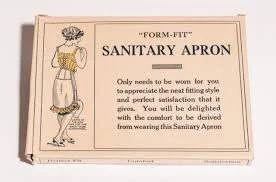

It wasn’t until the very end of the 19th century that commercial sanitary products began to emerge. Below are photos of a Sanitary Apron and a Sanitary Belt, both considered to be early mass marketed products. The belt was actually used in a modernised form until the 1970s and was designed to hold together disposable pads made of cotton and gauze.

Despite this tentative motion towards wider accessibility and use of hygienic sanitary products, particularly publicly, the gap between rich and poor experiences of menstruation widened. For those in workhouses, manufacturing floors were lined with sawdust and hay to absorb excess liquid, including period blood, as there was little option but to free bleed.

This introduced an inequality in terms of ease of day-to-day life, with poorer people unable to access newly developed products. However, it could be argued that, in comparison to modern emphasis on menstrual discreteness, this unavoidable free bleeding established an environment in which blood outside the body was normalised. In some ways, this may have eliminated the anxieties surrounding bleeding and leaking that menstruators using products marketed to disguise the presence of periods later began to face.

20th Century Commercialisation

The 20th century saw the rise of disposable menstrual products and the proliferation of mass-produced tampons and pads. In 1934 Tampax was founded by Gertrude Tendrich and in 1937, the first menstrual cup was invented by Leona Chalmers. However, production of the latter was halted by a rubber shortage caused by World War 2. (Luckily Chalmers’ idea was revived in 2002 into a modern hypoallergenic menstrual cup – the Mooncup!)

In 1985, Courtney Cox was featured in a Tampax advert and became the first person to say the word ‘period’ on television, signifying a cultural shift away from the hidden nature of menstruation within advertising and media. By the end of the century, products worked better, were cheaper to access, and allowed for menstruation to be less of a barrier. Importantly, products were now marketed and spoken about publicly, slowly working towards destigmatising menstruation.

However, it is important to note that the language associated with bleeding in such adverts, particularly those of the early 2000s, simultaneously reinforced stigmatised ideas of sanitised femininity and secrecy. Copy that focussed on the ‘discreetness’ and ‘freshness’ of products disseminated publicly the idea that periods were dirty and embarrassing, therefore encouraging a reliance on single-use sanitary products as a solution to boost the confidence of women. We may also recall the use of a blue liquid to demonstrate the absorbency of products, furthering this association of period blood as graphic and unclean through its on-screen omission. This illustrates the tension between the use of advertisements to open the conversations around menstruation, and the reality that their visual and written marketing only publicised existing societal stigma.

Today

Nowadays, there are countless options. Notably, modern-day products have a focus on their environmental impact, either through incorporating sustainable materials like bamboo, or encouraging reusability. Whilst it would likely be ill-advised to return to the days of papyrus pads, a focus on the ecological footprint of our sanitary items, without sacrificing their function and hygiene, seems like a beneficial combination.

Additionally, whilst theses advancements to the accessibility of period products are tremendous, there is still a long way to go. The World Bank reports that lack of menstrual hygiene facilities affects over 500 million people globally (2022). This gap in accessibility means that improvements in menstrual sanitation is yet to be felt worldwide, leaving some people to rely on unsafe and unhygienic alternatives.

As we look to the future, further improvements to sanitary products should be supported by efforts to reduce period poverty to ensure that menstruators worldwide can benefit from the increasing range of products to manage periods safely and without stress.

Sources:

The Women's Organisation. “The History of Period Products: From Censorship to Autonomy.” The Women’s Organisation, 5 Jan. 2024, www.thewomensorganisation.org.uk/the-history-of-period-products/.

V&A. “Sanitary Suspenders to Mooncups: A Brief History of Menstrual Products · V&A.” Victoria and Albert Museum, V&A, 2023, www.vam.ac.uk/articles/a-brief-history-of-menstrual-products?srsltid=AfmBOoodniJNa-qOO5XHzhpOgJj--XWmGiH-yS2VO_Bni_MkKuVDUXvJ.

Waldorf, Sarah, and Larisa Grollemond. “Getting Your Period in the Middle Ages.” Www.getty.edu, 2023, www.getty.edu/news/education-periods-facts-women-medieval-history-past-before-pads-tampons/.

World Bank Group. “Menstrual Health and Hygiene.” World Bank Group, 12 May 2022, www.worldbank.org/en/topic/water/brief/menstrual-health-and-hygiene.

If you enjoyed the article, check out the other ways you can support us!